In 1906, an ox, butchered and dressed, lies on a set of scales, while its butcher scratches a number onto a piece of paper, curiously matching the number calculated on another, very different piece of paper. In 1907 a man called Pablo enters his studio with fresh inspiration, touching brush to canvas and drawing the first hasty lines of a movement that would send ripples through history. In 1927, two of the greatest minds in history argue about electrons over breakfast in Brussels.

To Create

The word creativity conjures up images of renegade artists, of free thinkers; people at the avant-garde of ‘ideas.’ But more literally it means inventiveness, to use ideas to create something: you can’t make anything interesting and new without some kind of creative thinking, and that can take many forms.

In art, the line between what is and isn’t good is often pretty abstract. Because great art has no singular definition, it’s futile to get into an argument about whether Da Vinci or Michelangelo was ‘better’. But in marketing, success and failure are actually measurable by trends, share prices, and KPIs. This means that sometimes in creativity there truly is a ‘better’ and (in theory) a ‘best’ – that is, whichever option changes behaviour and sells.

How do we come to terms with the idea that creativity, a supposedly subjective enterprise, can be measured objectively? The answer is that creativity isn’t actually all that subjective. In reality, creativity is the finding of accurate solutions. Any accurate solution understands the problem entirely, and offers a well-considered action. Problems solved by art are inherently personal, situational, mutable, and so without a carefully restricted context, we can never declare whether one painting is truly ‘better’ than another. But if Dior launch a new fragrance and want lots of people to buy it there is always, in theory, a ‘best’ tv advert to sell it.

If that sounds a bit like a death march for creative thinking: it isn’t. While anyone can solve a problem, the magic of ‘creative’ people is their ability to draw ideas from a wider pool of possibilities – sometimes the best solution is simple, obvious; but often, the best solution is original; different; bold. That is to say: unexpected.

So therein lies the deeper question. Where do unexpected ideas come from?

\\\

The Runniness of Ideas

Picasso holds his brush, and begins to paint; where yesterday he had painted his figures with short, gentle daubs, today he paints using long, straight lines. Noses are where two curves meet, torsos are angular; mouths a straight line.

That painting, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, slowly took shape. It was unexpected. It was brilliant. Kicking and screaming, with powerful little lungs, Cubism was born.

Cubism crept across Europe and then swept across Asia, and kept sweeping until it was named the most influential art movement of the 20th century – and it was all, ultimately, because a man called Henri showed his friend Pablo a small Congolese figurine that he’d bought for a few pennies in a Parisian curio shop.

After all, that painting, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, had not come from nowhere. Years later, proto-Cubism was identified in the work of artists like Cézanne and Gauguin, who in the decade prior had become fascinated by the use of shapes like spheres and cones to build the organic world; it was a kind of structural minimalism which put simplicity over accuracy. But these baby steps looked nothing like what Picasso was painting.

Left: Les Demoiselles d’Avignon; Right: The African figurine shown to Picasso by Matisse.

Far from just abstractifying people and nature, cubism uses proportion to make simple forms more emotive, a marked departure from the European preference for clarity and realism that had presided over the past centuries. This abstraction of form was borrowed from African art, where figures are frequently distorted in striking ways, twisting the mundane into the moving by amplifying and subduing different aspects of the human anatomy – Cubism’s moment of inception, those first sketches for Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, had come just hours after Picasso examined that African figurine shown to him by Henri Matisse during a friendly house visit.

There are no artists who owe nothing to their peers, whom they collaborate with, compete with, inspire and are inspired by. Andy Warhol even got the idea for his iconic Campbell’s Soup Cans from his friend Muriel Latow, when Warhol offered to pay her for the first idea she could think of. (The cheque was for just $50.)

Far from a fluke, Latow – an art expert and gallery owner – was credited with inspiring many artists at the time, and was a close friend of Mark Rothko, who attributes the inspiration for his iconic abstract paintings to seeing Matisse’s Red Studio. Matisse, in turn, credited his revolutionary style to John Russell; Russell was a close friend of Vincent Van Gogh; Van Gogh of Gaugin; Gaugin, who influenced Picasso, also knew Cézanne, who knew Monet, who knew Renoir, who borrowed from Manet, and so on and so on for ever and ever.

Ideas are liquid. They drip and flow wherever permitted, and as people dip their toes in at their shores they etch fresh channels with the footprints they leave behind – inch by inch connecting the as-yet unconnected.

Pablo was already well familiarised with many forms of African art; but when Matisse showed Picasso the figurine, Picasso for the first time splashed in the possibilities of what could be, taking the striking, evocative form of the figurine and carrying it over to his canvas.

The benefits of inspiration shared are not just an artist’s thing: a study of 1500 scientific papers found that the novelty of the article was heavily dependent on the size of the research team. They found that the large teams were more able than small teams or lone researchers to pull from a wide range of inspiration, blending ideas from a variety of different fields together in original ways. This helped them push their fields forward in interesting ways.

The first offices were originally venues of convenience. Scribes worked where the scrolls were kept, bankers where the accounts were kept, manufacturing managers where they could keep an eye on the production line; but as creativity became taken more seriously across the 20th century, office architects began to borrow elements from artists’ studios: walls were lowered or removed entirely, desks became moveable, space was made for play. Offices got weird.

A far cry from the compartmentalising cubicles of the 50s, modern offices are meticulously designed to let people talk, and share, and discuss, and play. This can seem like a nightmare when we just need to get it done; and yet whenever we’re faced with the question “but how?” the creative space within the office can be a not-so-secret ingredient.

\\\

Progress, by Popular Demand

Looming over the ox’s remains, a butcher makes some careful final adjustments to his scales, then tallies up the numbers, underlining the bottom figure. A moment later he smiles, as if someone has just told him a good joke. He circles the number, for emphasis: 1197 lbs.

A few days before, when the ox had stood – very much alive – at the centre of the 1906 West of England Fat Stock and Poultry Exhibition, in Plymouth, England, nobody knew its weight. And yet, by the end of the fair, the audience had successfully determined exactly (to the pound) what the ox weighed.

How? The wisdom of the crowd.

At the fair, a Guess The Weight Of The Ox contest was being held; punters could pay six pennies to submit a guess, and the closest estimate won a grand prize. At the end of the fair, with over 700 guesses made, Francis Galton (talented statistician; inventor of eugenics) had heard about the contest, and asked the farmer to analyse the submissions, hypothesising that the crowd, collectively, might produce a very good guess. The guesses varied wildly – from 300 lbs too high to 300 lbs too low. But underlined in the statistician’s faded notebook, the average had not just produced a very good guess, but a perfect one: 1197 lbs.

Humans are quirky, each with our own snowflake of biases, opinions, and irrationalities. Where the judgement of one person is something to be sceptical of, collectively we can help to balance each other out. A wayward guess isn’t rejected, it’s simply countered with other, oppositely wayward guesses, and in the crowd, biases are slowly cancelled out, making our educated guesses ever more accurate.

And so when one becomes two becomes three, and company becomes a crowd, we iron out our wrinkles. We make ourselves more like the median member of our target audience: another uniquely average person, going about their day.

When we have the core of a truly great idea, we need to pick the direction to take it in. There are infinite possibilities. Many will bore. Some will disgust. A handful will suffice. And only a few will work. We’re lucky in marketing that success/failure can often be measured, and so rather than flying blind we’re blessed with the fact that there really can be a ‘best’ – and certainly a ‘better’. Creative judgement has to be exercised vox populi; bad suggestions politely laid to rest, and good suggestions allowed to flourish.

And so crowds are wiser than people – for the most part. Crowds are smarter when they are diverse, offering a wide array of perspectives and biases. Crowds are smarter when they are well-informed, having been told all the relevant details about the problem at hand. And crowds are smarter when they are experts, with experience to guide them.

But it should be noted that crowds can be imperfect. The anchoring effect can mean that the people who speak first or loudest can create a gravitational field that pulls the group towards them, away from other, potentially brilliant ideas. And any crowd should be careful to know thyself, because any pre-existing biases shared across the whole group can actually be exacerbated by discussion.

In creative environments, to work all alone is to be walking blind; our biases can lead us astray, and often the only thing that can pull us back on track are the different biases of our coworkers and friends. A team of half-blind creatives can make it to the finish line if only they listen to each other, and stop one another from wandering off the cliff.

\\\

Trial by Kiln

“God doesn’t play dice!” insists Einstein, throwing his hands in the air.

“Stop telling God what to do,” replies Niels Bohr evenly.

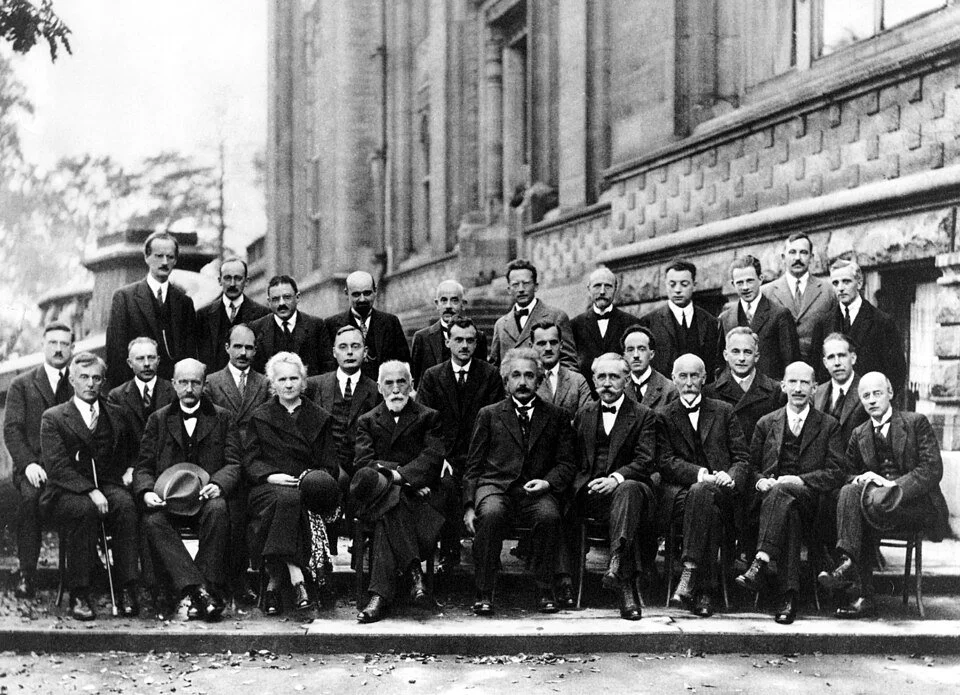

The year is 1927, and two friends are arguing. Now a fixture of scientific folklore, the Einstein–Bohr debates advanced the field of quantum physics by years, taking place at the Solvay Conference in Brussels, Belgium – an event referred to by some as the largest assembly of great minds in all of history, with 19 of its 27 attendees receiving a Nobel Prize in their lifetime. Bohr is insisting that photons and electrons are indeterminate – they only have fixed physical properties after being observed. As strange as it seems, a photon simply doesn’t have a position or momentum, until someone takes the time to try and measure it.

Einstein proclaims this ridiculous: a planet orbits a star with a speed and a position, always – regardless of whether someone on Earth has used a big telescope to look at it yet. A cat in a box is either alive or dead – not both simultaneously until someone bothers to check on it. To claim otherwise is ridiculous. Photons are much the same.

The days started over breakfast, with Einstein conjuring a complicated thought experiment that he believed disproved Bohr’s ideas; discussion raged through the day as Bohr deflected and countered, batting aside each of Einstein’s quibbles, and by dinner, Einstein was usually looking worried. The next morning however, at breakfast, he would be calm and composed, regaling them with another, even more convoluted thought experiment that Bohr would surely concede to this time.

The 1927 Solvay Conference Attendees. Einstein is pictured front row, fifth from the left; Bohr is in the second row, on the far right.

Einstein, ultimately, was wrong. His contribution to quantum physics wasn’t to rewrite it; it was to deepen it, to provoke its supporters to add detail to their theories, expanding them to be able to deal with even the wackiest of scenarios he was dreaming up. His genius strengthened Bohr’s theories, improving them, refining them. Today, the conclusions of this debate – and Einstein’s contributions – underpin lasers, MRIs, GPS, flash drives, computers, LEDs, and are directly used in quantum computing.

Authors are often thought of as particularly solitary artists. Yet one of the greatest works of fiction of all time, Tolkein’s Lord of the Rings was perfected only with the help of his writing group, The Inklings, who met up once or twice a week to workshop their various scribblings. This group shaped his work not just on a few occasions, but over years; his writing on the trilogy started in 1937, and was only completed in 1949.

This process of feedback, iteration and development is used everywhere: the same study that found the link between novelty and team size also found that a larger team size increased the impact of a finding. While there are a few reasons for this, it’s certainly the case that bigger teams can help to refine research, making it ever more bulletproof, giving it the best chance of sticking the landing with its audience.

And so it goes in the imagination industry: Nike and Apple produce some of the most popular work in the world – not by relying on a handful of geniuses, but by having a strong structure that allows a large number of talented, trusted eyes to look at something and suggest improvements before it’s ever officially stamped with a swoosh or iProduct label.

When a bold idea is taking shape, it needs considered collaboration to give it every chance upon its release into the world.

\\\

Thinking with Our Ears

So what is it that great innovators do better than anyone else? They listen.

When Picasso was told by Matisse about the figurine, he listened. Individually, the crowd at the Cattle Fair produced 787 wild guesses – their collective genius was only unlocked once they were asked. Each morning at breakfast when Einstein outlined his new challenge, Bohr was there, attentive.

This process of moving from ideation, to judgement, to iteration is not a straight path we walk down, but a cycle – one that on bad weeks never seems to end – that inches us closer and closer to the destination every time we revolve through it. And listening is an essential part of each stage of the journey.

We listen to the world, to our friends, pocketing stray ideas to generate wacky ‘starter’ thoughts that take us somewhere interesting.

We listen to the room, knowing that somewhere in the middle between the mess of our differences, there is truth and insight.

We listen to and embrace challenges and challengers, to understand how we can build a more perfect idea.

The offline world should be celebrated, not as a place of productivity, not as a place to talk; but a place to listen. In our daily chatter there are all sorts: golden nuggets, beautiful junk, weird truths and loose wisps of genius, if only we know how to find and hold onto them. Close contact is essential to generate, develop and hone great ideas.

The world’s belated acceptance of both on- and offline work has been essential, a step into the future, but the office is not the best place for everyone, everywhere, all of the time. The internet has given us so much; but subtlety, clarity, and side conversations are too easily lost in the world of Teams and Zoom.

Just as the advent of radio and the TV at first seemed to threaten the existence of the classroom (so much cheaper to broadcast one teacher to the whole nation!), a few video conferencing apps have presumed to upturn the globe

The internet revolution has at long last lobotomised the insane presumption that nothing worthwhile can be done without sitting in a bus, tube, or car for an hour or so each day. But offices, parks, and libraries will keep their rightful place as havens for any group of people with a creative mission. Balance may be king, but human connection will always reign supreme.